Key Takeaways

- “BPA-free” plastic means a product was made without bisphenol A, but it may still contain similar chemicals like BPS or BPF that carry similar risks.

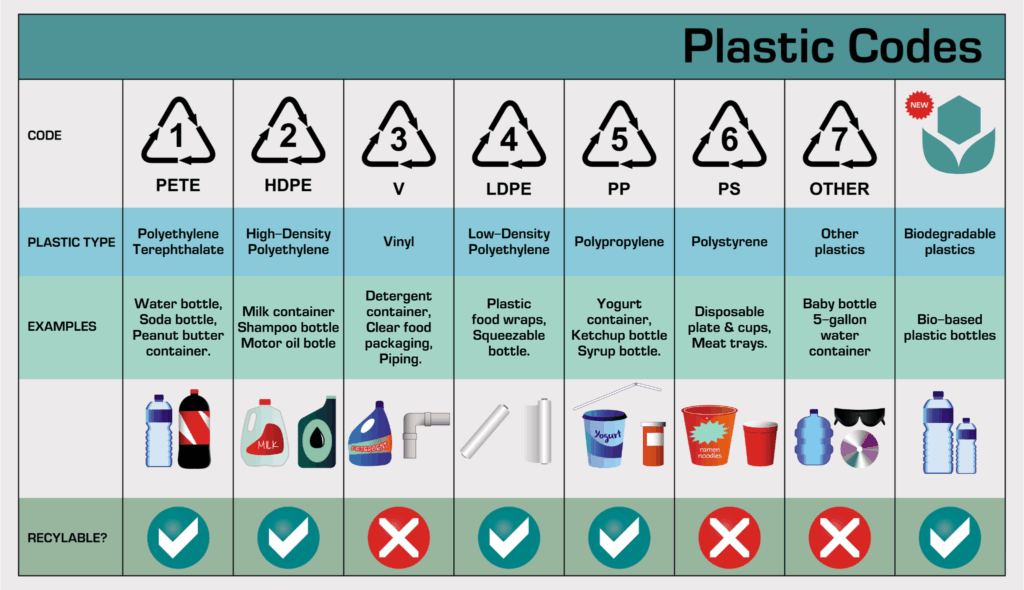

- To tell if plastic is truly BPA-free, check recycling codes — choose 1, 2, 4, or 5, and avoid 3 and 7 whenever possible.

- Glass, stainless steel, ceramic, and food-grade silicone are safer long-term alternatives that help reduce both health risks and plastic waste.

Did you know that almost everyone tested has BPA in their body? A major U.S. health study found traces of bisphenol A (BPA) in 93% of Americans, and European researchers found similar results across 11 countries. That means nearly all of us are carrying small amounts of this common plastic chemical without realizing it.

BPA has been used for decades to make plastics clear, strong, and heat-resistant — showing up in everything from food containers to receipts. But research has linked it to possible hormone disruption and other health risks, which is why so many products now claim to be “BPA-free.”

The problem? “BPA-free” doesn’t always mean safe. Some plastics labeled as BPA-free still contain similar chemicals that can act the same way in your body. This guide breaks down what BPA-free really means, how to tell if a plastic is safe, and which materials are genuinely better for your health and the planet.

What Is BPA-Free and Why Is It Used?

BPA, short for bisphenol A, is a chemical used to make certain plastics and resins strong, clear, and durable. It’s what gives many plastic bottles their smooth, glass-like look and helps keep food can linings from rusting or breaking down.

Manufacturers started using BPA because it makes plastics rugged yet lightweight — perfect for water bottles, food containers, and even baby bottles. It also keeps metal cans from corroding, which helps food last longer on the shelf.

The problem? BPA doesn’t stay locked inside the plastic. Over time, it can leach into food or drinks, especially when containers are heated, scratched, or worn out. That’s why BPA has become a significant health concern and why you now see so many products labeled “BPA-free.”

Where BPA Is Commonly Found

BPA hides in more everyday items than most people realize. Because it makes plastics durable and helps prevent metal cans from rusting, it has ended up in all kinds of products we use daily. Here’s where it often shows up and what to look out for:

🥤 Plastic food containers and bottles – Older or lower-quality plastics can slowly release BPA into food and drinks, especially when they’re heated, scratched, or worn out.

🥫 Canned foods and drinks – The thin inner lining that keeps cans from corroding often contains BPA-based resin, which can leach into soups, sauces, or sodas over time.

🧾 Thermal paper receipts – Those shiny store receipts are frequently coated with BPA, which can transfer to your skin during handling.

🧸 Household plastics and toys – BPA can still be found in older kitchenware, reusable bottles, and some children’s toys made before BPA-free standards became common.

💧 Water cooler jugs and refillable containers – Some large, rigid plastic jugs and dispensers use polycarbonate plastic, a primary source of BPA.

Is BPA-Free Plastic Safe?

When you see a product labeled “BPA-free,” it’s easy to assume it’s completely safe, but that label can be misleading. “BPA-free” simply means the product doesn’t contain bisphenol A, the original chemical used to make plastic strong and clear. It doesn’t guarantee that the plastic is free of other potentially harmful compounds.

The Problem with BPA Substitutes

To keep plastics durable and heat-resistant, many manufacturers now use replacements like BPS (bisphenol S) and BPF (bisphenol F). These substitutes were meant to sound safer, but early research suggests they may behave in similar ways, disrupting hormones, affecting metabolism, and even influencing brain function. Scientists are still studying these chemicals, but the results so far point to caution rather than confidence.

Why “BPA-Free” Doesn’t Mean Risk-Free

Even if a product is made without BPA, other additives in the plastic can still leach into food and drinks, especially when exposed to heat, acidity, or wear and tear. Microwaving food in plastic containers, leaving water bottles in a hot car, or using scratched containers can all increase your exposure to these chemicals.

Making Informed Choices

Avoiding BPA is a smart first step, but the safest approach is to limit plastic use altogether whenever possible. Choose glass, stainless steel, ceramic, or food-grade silicone for food and drink storage, and look for trusted third-party certifications such as NSF, MADE SAFE®, or OEKO-TEX® when buying new items.

The bottom line: “BPA-free” is progress — but it’s not a promise. Understanding what the label really means helps you make safer, more informed choices for your health and the planet.

safe plastic use

Tips to Reduce Chemical Exposure

Even BPA-free plastics can release chemicals, especially when misused. Here are the most important safety practices:

- Avoid Heat: Never microwave plastic containers or leave them in hot cars. Heat causes plastic to break down and release more chemicals into food and drinks.

- Watch for Wear: Replace scratched, cloudy, or cracked containers immediately. Damaged plastic leaches significantly more chemicals.

- Smart Storage: Use glass or stainless steel containers for acidic foods (such as tomatoes and citrus) and fatty foods (like oils and butter). These can pull chemicals from plastic.

- Choose Safer Codes: When you must use plastic, stick to recycling codes 1, 2, 4, and 5. Avoid codes 3 and 7.

- Hand Wash Only: Skip the dishwasher unless the container is specifically labeled dishwasher-safe. Hot water and harsh detergents accelerate chemical breakdown.

How to Identify BPA-Free Products

Figuring out whether a plastic item is truly BPA-free can feel confusing at first, but there are a few simple checks that make it easy. Once you know what to look for, you can quickly tell which plastics are safer and which ones to skip.

Step 1: Check the Label (But Don’t Stop There)

Start by looking for a “BPA-free” label on the packaging or product itself. Many newer containers, bottles, and baby products proudly display it. This is a good first sign, but remember, it only means the product doesn’t contain bisphenol A. It doesn’t rule out other similar chemicals like BPS or BPF.

If you don’t see any markings at all, especially on older plastics, that’s a red flag. Unlabeled products are more likely to contain BPA or other bisphenols.

Step 2: Look at the Recycling Code

Flip the product over and find the small triangle with arrows and a number inside. This is the recycling code, also called the resin identification code, and it tells you what kind of plastic was used.

Here’s what those numbers mean and which ones to trust:

✅ Safer Choices (Generally BPA-Free):

- 1 (PET or PETE): Used in single-use water or soda bottles. Doesn’t require BPA in manufacturing.

- 2 (HDPE): Common in milk jugs and detergent bottles. Durable and chemically stable.

- 4 (LDPE): Found in plastic wraps and squeeze bottles. BPA-free and flexible.

- 5 (PP): Used for reusable food containers, straws, and bottle caps. Heat-tolerant and BPA-free.

❌ Use Caution or Avoid:

- 3 (PVC): Can contain BPA and phthalates used to soften the plastic.

- 6 (PS): Often used for disposable plates and foam cups; may leach styrene, another concerning chemical.

- 7 (Other): A mixed category that often includes polycarbonate plastics, the primary source of BPA. If it’s clear and rigid, assume it could contain BPA unless labeled otherwise.

✨tip

Can’t Find the Code

If you can’t find the recycling code, feel around the bottom of the container. It’s often embossed rather than printed.

Step 3: Look for Trusted Certifications

Some third-party certifications confirm that a product has been tested and meets strict safety standards. Here are a few to look for:

- OEKO-TEX® Standard 100 is a globally recognized certification for textiles that ensures they are free from harmful substances, including BPA. Products bearing this certification have undergone testing for a wide range of chemicals, ensuring they meet stringent safety standards for human health.

- NSF certification is a trusted standard for product safety and quality, particularly for items related to food and water. This certification ensures that products meet stringent public health guidelines and have been tested for the presence of harmful substances, including BPA.

- MADE SAFE® Certified is a comprehensive, third-party certification that ensures products are made without toxic chemicals known to harm human health or the environment. Unlike some certifications that focus on a specific category, MADE SAFE® applies to a wide range of everyday products, including personal care items, household goods, baby products, and even bedding.

Step 4: Watch Out for Greenwashing

Just because a product says “BPA-free” doesn’t mean it’s completely free from harmful chemicals. Companies sometimes replace BPA with similar bisphenols (like BPS or BPF) without disclosing it. Marketing phrases like “safe plastic” or “eco-friendly” can be vague. Look for specific material listings, such as Tritan, polypropylene, glass, or stainless steel, for a safer bet.

Step 5: When in Doubt, Ask

If you’re unsure about a product’s safety, especially if it is labeled with code #7 or has no marking at all, check the manufacturer’s website or contact their customer service. Reputable brands are often transparent about their materials.

Don’t Miss: What Is Tritan Material? Curious about Tritan, the popular BPA-free plastic used in bottles and containers? Find out how it compares to other materials and whether it’s really safer. Read more →Safer Alternatives to Plastic

While BPA-free plastic may seem like a better choice, it often contains substitute chemicals like BPS or BPF, which may carry similar health risks. The most reliable way to reduce exposure to harmful substances and limit environmental impact is to reduce plastic use altogether. Safer, more sustainable materials include:

- Glass – Non-toxic, non-reactive, and free from harmful chemicals. It won’t absorb flavors or odors, and it’s dishwasher-safe. Great for reheating food in the microwave, as it handles heat well and doesn’t degrade over time, keeping it safe from drops.

- Stainless Steel – Durable, long-lasting, and great for food storage, water bottles, and cookware. It’s resistant to rust and chemical leaching; however, some containers may have plastic lids or linings, so it’s worth checking before purchase.

- Silicone – A flexible, lightweight option for lids, baking mats, and food storage. It’s heat-resistant and reusable, although some concerns remain about its safety at extremely high temperatures or over prolonged use. Look for food-grade, platinum-cured silicone for the safest option.

- Ceramic – Another plastic-free choice that’s ideal for reheating and storing food. It’s naturally non-toxic and doesn’t leach harmful substances, though it can be heavy and prone to chipping.

Choosing safer materials not only helps protect your health but also reduces the amount of plastic waste generated in your home.

Don’t Miss: The Truth About Plastic — Why Plastic-Free Living Matters Read this next to discover why finding plastic-free alternatives is so important for your health and the planet. Read more →FAQs on How to Tell if Plastic Is BPA-Free

Usually, yes — BPA-free or non-plastic products like glass and stainless steel can cost a bit more upfront. But they’re also more durable, reusable, and long-lasting, so you’ll save money over time by not replacing them as often.

Yes. Even if plastic doesn’t contain BPA, it can still release other chemicals when heated, scratched, or exposed to acidic foods. Research shows that substitutes like Bisphenol S (BPS) and Bisphenol F (BPF) are nearly as hormonally active as BPA. So BPA-free is a step forward, but it’s not a guarantee of zero risk.

Plastics labeled with recycling codes 1 (PET), 2 (HDPE), 4 (LDPE), and 5 (PP) are generally considered safer and less likely to contain BPA. Avoid 3 (PVC) and 7 (Other) unless the product says explicitly “BPA-free.”

Research indicates that BPA acts as an endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC), meaning it can mimic or interfere with hormones in the body. Studies link it to reproductive, metabolic, and developmental concerns. While small exposures may not cause harm for most adults, reducing overall contact, especially for babies and pregnant people, is a wise precaution.

Use glass, stainless steel, or ceramic for food and drink storage instead of plastic. Avoid microwaving food in plastic or storing hot liquids in plastic containers, as heat increases the leaching of chemicals.

Minimize handling of thermal-paper receipts, replace scratched or cloudy plastic containers, and choose fresh or frozen foods instead of canned goods. When you must use plastic, stick with recycling codes 1, 2, 4, or 5 and avoid 3, 6, and 7.

This Has Been About How to Tell if Plastic Is BPA-Free

Ultimately, BPA-free plastic isn’t the perfect solution. While it’s better than BPA-filled plastic, many alternative chemicals have their concerns, and plastic, in general, still poses risks to both our health and the environment.

The best way to avoid uncertainty is to choose non-plastic options whenever possible. Glass, stainless steel, ceramic, and high-quality silicone are all safer and more durable choices, free from hidden chemical concerns. Plus, they last longer and don’t contribute to the endless cycle of plastic waste.

So, while reading labels and choosing “less harmful” plastics can help in the short term, the real solution is moving toward a plastic-free lifestyle. When it comes to our health and the planet, opting for plastic-free choices is always the smartest choice.

📚 References

- Calafat, A. M., Ye, X., Wong, L.-Y., Reidy, J. A., & Needham, L. L. (2008). Exposure of the U.S. population to bisphenol A and 4-tertiary-octylphenol: 2003–2004. Environmental Health Perspectives, 116(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.10753

- European Environment Agency. (2023, April 5). Public exposure to bisphenol A above health safety levels. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/newsroom/editorial/public-exposure-to-bisphenol-a

- Gauthier, J. M., Brody, J. G., & Rudel, R. A. (2014). Bisphenol A and human health: A review of the evidence. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122(8), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408989

- Wang, Y., Li, J., & Liu, C. (2021). Microplastics in the environment: Sources, fate, and toxicity. Science of The Total Environment, 791, 148383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148383